Like many people, I played a lot of Animal Crossing: New Horizons in 2020. Eventually, though, I walked away from my island, with its carefully terraformed ponds and a half-built castle and an entire rainbow of flowers. I have no desire to go back. It’s so much work! So much weird pressure to make everything just right. To collect all the things. To pay off to that capitalist racoon, Tom Nook.

A little over a month ago, I started playing a game called Cozy Grove. Cozy Grove is like Animal Crossing without the capitalism. (Mostly.) You still buy things and craft things and get flowers and trees and a lot of stuff. (There are cats, and they really like stuff.) But helping the ghost bears who live on the island of Cozy Grove is the heart of the game, and it makes a huge difference in how it feels. You run their errands, find their stuff, listen to their stories (or conspiracy theories), help them figure out who they were and what they need. It’s a game of small kindnesses and big feelings, a place where figuring yourself out, mistakes and all, is key.

In that way, it’s kind of like a Becky Chambers book. It’s a world where flawed people deserve love and connection, where kindness and hope spring eternal, where you can make interspecies friendships and find adventures through small gestures. These are the kind of worlds I want to live in, right now—worlds that give us permission to be human, in the sense that to be human is to be flawed and imperfect and full of messy feelings that don’t always have anywhere to go. To want and need and love and struggle and hope on a human scale, one that rarely concerns the fate of worlds or the actions of a chosen one. To walk through a world—ours or another—more gently.

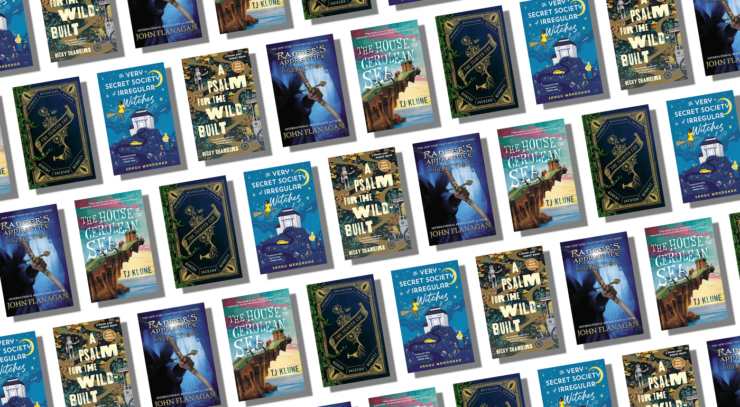

This feeling always existed in Chambers’ work, but has reached new heights in her Monk and Robot books. The premise is simple: in a thriving, harmonious world, Sibling Dex has a bit of a crisis. “Sometimes,” A Psalm for the Wild-Built begins, “a person reaches a point in their life when it becomes absolutely essential to get the fuck out of the city.”

It’s a beautiful, wonderful city—the only City—but Dex needs something new. They decide to become a tea monk, traveling around listening to people’s problems and serving them tea. Out in the wild world, Dex encounters something truly unexpected: a robot named Mosscap. Robots, in this world, gained sentience centuries ago and took off into the wilderness. They haven’t spoken to humankind since. But Mosscap has returned to ask one simple and difficult question for humanity: What do people need?

What do people need? Dex doesn’t know. Dex doesn’t even know what they themself want, exactly. (Dex is extremely relatable.) In Psalm, Dex and Mosscap have a lot of conversations about people and the world we live in. Things that we take for granted, things that humanity has, generally speaking, really fucked up—these things are fascinating to the robot, who is “wild-built,” made out of the parts of previous generations of robots. Mosscap has never experienced people. Mosscap has never experienced a lot of things. Everything is fascinating. Everything is wonderful. This could, if you were Sibling Dex, get a little exhausting. But Chambers knows how to pace a story, knows how to give just enough of Mosscap’s endless curiosity so that we’re reminded just how many things there are to be curious about—how many things we walk past, in any ordinary day, and yet don’t understand.

In the second Monk and Robot book, A Prayer for the Crown-Shy, Dex and Robot make their way back to the towns of Panga so that Mosscap can pose his question to other people. What do they need? People need help with chores and tasks. They need small things, mostly. Practical things. This society trades for necessities and people look out for each other in ways big and small. The harder question is one Mosscap doesn’t really know how to frame: What else do you need when your basic needs are met? Do you really need more? What kind of more?

And what does a robot need?

Little things happen in these books, and they feel momentous. Mosscaps learns about the world’s trading system. It marvels at trees, reads everything, stops for every flower. On a very good day, I can feel a little like Mosscap, walking around my neighborhood with an eye out for every hummingbird, every new bloom of lilac, every creaking crow and stranger’s garden; the way one house has a plastic pony tied up out front and another offers a “creature swap,” a shelf full of small toys for the local kids to trade. On a bad day I just see the weeds and the gloom, dripping gutters and mossy roofs, potholes and low-hanging clouds.

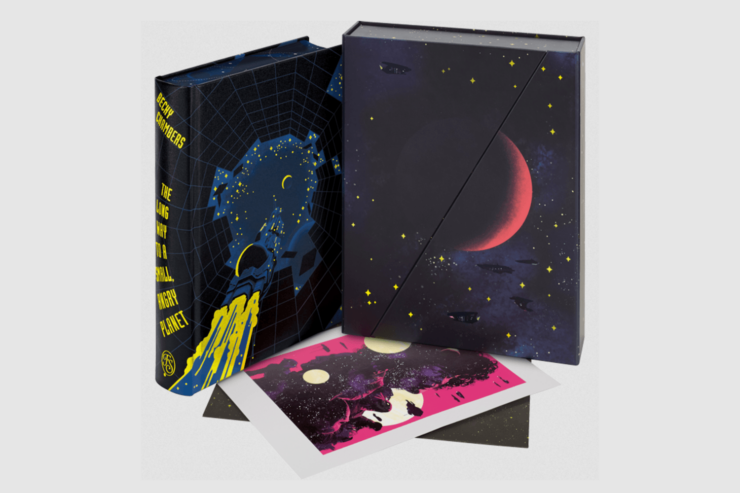

This specificity, this understanding of the small, often intangible things that make a day good or bad, hopeful or bleak, has run through Chambers’ work since The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet. I picked up The Long Way up for a quick brush-up and before I knew it, I was 150 pages in and entire re-engrossed in the lives of Rosemary Harper and the rest of the crew of the Wayfarer, a ship full of people (of several species) with a job to do and a lot to talk about. The galaxy, in this series, is not a place colonized and dominated by humans. We’re just kind of … there, among all the other, more powerful species. We are small and argumentative and unimportant. We are not saving the universe.

It’s really very refreshing. Haven’t we ordinary folks got enough problems of our own? And aren’t those problems—the personal ones, as well as the big ones—valid and meaningful? Do we not deserve adventures and found families and new kinds of freedom even if we aren’t “heroes” and superstars? Every one of Chambers’ books says yes, both for her characters and for people, in general. Every story is an epic; every person is a galaxy.

And then there’s To Be Taught, If Fortunate, a book that will very gently tug at your every heartstring until they’re all singing and you feel like you’re vibrating at a whole new frequency. It follows the journey of a quartet of astronauts who blasted off from Earth in a future wracked by climate change, but also shaped by collaboration. Their company is funded by everyone who believes in space travel, from the very wealthy down to the people who just donated their beer money to the cause. Ariadne, Jack, Elena, and Chikondi are on a mission to visit planets, study their native species while leaving no footprint, then travel to the next planet to do it all again.

It’s simple. It’s endlessly complicated. The book is narrated by Ariadne, an engineer, who’s speaking to us—an “us” she can’t really define or know—from an uncertain future. It’s a story, but it’s also a report on their mission, and it becomes more or less personal at different times, more or less intimate, more or less focused on the science or the people. But throughout, it’s a story about connection, grief, isolation, and how feeling trapped and lost in your own life can feel like being stuck inside a spaceship that’s being gnawed on by screaming alien rats.

Where The Long Way was very focused on its crew, To Be Taught is as much about everyone who isn’t aboard the Merian. It’s about those left behind, those whose fates are unknown. Us, basically: the people of the past, whose future is still a big looming question mark. What will we choose for this world, which is still the only world we have, no matter how many other amazing planets are out there? How do we hold onto hope in the face of the unknown?

Chambers is a genius at recontextualizing what matters, what’s hard, what affects us, what we have to endure and who we are when we come through it. A spaceship is a home; a ship’s crew is a family; a robot is the only being capable of asking us a question we might have forgotten to ask ourselves. And part of the reason she can explore all these things so deftly is that she creates worlds in which just being ourselves is a given. Everyone is different—species, sexual desires, cultures, habits, quirks, appearances—but none of these things are issues. Often, they aren’t even defined. People just are who they are. In these worlds, we don’t have to explain ourselves. But we still need to understand ourselves. Her work asks its own question: What would a better world look like? How can we work toward it?

“I write the stories that I need to hear,” Chambers said in an interview last year. “The harder things in my own life are, the more likely I am to lean into writing about people who grow and heal.”

And they’re not just stories about people who grow and heal, but stories that center that growth and healing. The Long Way is about growing up and growing into yourself (among other things); To Be Taught is about facing loss and grief and finding ways to heal and hope and keep growing despite everything. The Monk and Robot books feel like fables about a kind of growing and healing that goes beyond ourselves and into our worlds and communities—making Chambers’ work all one process, a growing up and out, a way of becoming more ourselves, but still human, and still with all our flaws.

These stories make me feel like it’s okay: okay to be human, okay to be confused, okay to make mistakes and missteps on the endless journey of figuring shit out. It’s okay to be human, with all that entails: ignorance and selfishness and secrets and shame right alongside love and empathy and curiosity and the promise that there is always something new, something more out there. There’s always a new way to understand who and what we are.

If there is one thing I feel slightly weird about in saying that Chambers’ books give us permission to be human, it’s that word: human. It’s a key part of her storytelling that we aren’t the center of things—not the planet, not the universe, not the story of this world. But there’s humanity, and then there’s the idea of “being human,” which to me means a lot of complicated and messy things: being fallible, self-aware, imperfect, hopeful, and full of potential. Part of what makes Chambers’ work so expansive, so open and loving and welcoming and big, is that none of these traits are specific to humanity itself. Robots, AIs, alien species, even plants and weird screaming alien rats are all treated with the same respect—and awe. Every new life form is a source of wonder to the scientists of To Be Taught. Every tree is a source of wonder to Mosscap. It’s amazing that any of these things exist.

It’s amazing every single one of us exists. To say that might sound impossibly hokey, like a sci-fi greeting card. But viewed through Chambers’ sharp eye and rigorous mind, it becomes something else—something that encompasses the role of science, the need for clarity and kindness and inquisitiveness, and the simple fact of human smallness, the fact that we’re just clinging to this rock for a brief time. It becomes wise and reassuring, a reminder as big as the galaxy and as small and comforting as a hot cup of tea.

It’s amazing that we exist, no matter how flawed, no matter how imperfect, no matter how many times we stumble. It’s amazing what we, as a species, still might do—and still might mess up. Hopefully we’ll learn to be wrong. We’ll learn to step back and sit down. We’ll learn, eventually—along with Mosscap, along with Dex, along with all the troubled bears of Cozy Grove—what we actually need.

Originally published in July 2022.

Buy the Book

A Psalm for the Wild Built